In the last month, I had a serious problem with my home internet connection for a few weeks. People don’t appreciating what they have until they loose it. Essentially, same happened to me when I lost the internet for a couple of days. I immediately begin appreciating this luxury of having stable connection while downloading every single kilobyte.

Web with limited access

One major challenge in developer daily work, apart from regular online meetings and constant communication, is access to required documentation of services often working with. Many of documentation project are usually easily available online, so normally nobody even think about use them without internet. But what if you would have a very limited internet access or even not at all?

This situation I’d been get into, encouraged me to quickly find a solution in order to my limited mobile bandwidth and not use all at once. I started by finding all the documentation for the services I mist working with and putting them into single lists for later download.

I get the list and promptly reached the place with the nearest stable internet connection. I get started pulling all docs with the neat plan to compile them and serve them on my local machine using docker containers.

Some fragment of the documentation list you can find below:

- jsdoc.github.io

- SVGOGM a missing GUI for [svgo]

- tailwind for v3 (and v4)

- material UI

- react-hook-form

- react-icons

As I mentioned before, I started with downloading all of them and testing if I could run them offline. However, the funny thing after downloading some of the docs, I realized that wasn’t the end of pulling new things. Usually, the files are just source files without any dependencies. Usually later you need to pull another bunch of dependencies required for each project to start. And to make it even more complex, each project might use a different way of installing its own dependencies. Moreover, some projects have dependencies that have their own dependencies, and then things can get complicated.

FUN FACT: After realizing this, I figured out that it would be actually pretty cool if every major project had an offline documentation image that could be easily pulled with one click. That would be very helpful for a consumer like me, who finds themself in the situation of being temporary offline.

The project dependencies were one aspect of the problem. The most challenging part was discovering a proper way to compile and build all those documentation projects. Each had its own unique approach, but some stood out as particularly difficult. The react-icons project proved especially troublesome due to its multi-step compilation process, which often resulted in errors. Tailwind posed another significant challenge, not due to the compilation process itself, but rather its substantial build size, which frequently required me to free up disk space after multiple failed attempts.

Dockerization process

Let’s take a look at the first example with the JS docs, available at jsdoc.github.io. This repository is actually very simple and easy to dockerize, so I will start with this one as an example. It will be easy to demonstrate how we can achieve our goal.

Also, before dive deeper into example, it’s worth mentioning that for creating Dockerfiles (or actually, in the end, Docker images), there are two major ways of doing this:

- The faster way, but less elegant and sometimes faulty - usually done by utilizing a spinning dev server inside the container. Those images are relatively much larger due to containing all of the dependencies required for running the server.

- The slower way, although producing smaller and more efficient images - by compiling source files and serving them statically with reliable servers like Nginx, for example.

I will start with the first way, also known as the “quick and dirty” method, to get some fast results. Later, I will do another example using a more efficient way of compiling and serving the content with previously mentioned Nginx.

Big and dirty image

As I mentioned, this way of creating containers is fast, although big and dirty as well. I would not recommend using it in production environments. Usually, the images are very large and inappropriate for end-consumer users. Although, for our purposes to serve documentation locally, it’s totally fine.

cd workspace

git clone git@github.com:jsdoc/jsdoc.github.io.git

cd jsdoc.github.io

# create our own Dockerfile

touch Dockerfile

Now that we’ve pulled the project, we can open a freshly created Dockerfile which will help us dockerize our documentation.

FROM node:22

WORKDIR /app

COPY ./package.json /app/package.json

COPY ./package-lock.json /app/package-lock.json

RUN npm install

COPY . .

EXPOSE 8080

CMD ["npm", "run", "serve", "--", "--port", "8080"]

PRO TIP: When creating Dockerfiles, I strongly recommend using hadolint linter. This library will greatly help you enforce best practices for creating great Dockerfiles. Please don’t be surprised if many of your current practices are discouraged or rejected – but hey, it’s all about creating files that are best for team work and future maintenance, right?

In here it would be worth to mention that for building Docker images that does not contain anything unwanted, very helpful is to create additional .dockerignore file. The purpose of this file is to block files from its list into the Docker container. Simple but very useful technique to make container “relatively” lightweight.

.git

scripts

*Dockerfile*

node_modules

.env

Now build the documentation and start a Docker container on port 9001.

docker build -f Dockerfile -t jsdoc:latest . && docker run --name jsdoc-offline -p 9001:8080 jsdoc:latest

That’s all for “the fast and dirty” creation of docker image. Let’s jump to the next section of creating more effective Docker image.

The effective way

Actually, I think it would be even more great to recreate the same documentation using a more effective technique and compare the results together. I’d be most excited about seeing the final sizes of the Docker images. We could also test the performance, although that would be rather an objective test of the servers running under the hood than a measuring of our benefits - a runnable image that we as clients just want to use.

So let’s start by recreating the previous solution using a more effective way.

In this process, we usually have a few steps:

- In the first step, we create a container where we actually pull all dependencies needed for the process of compiling the documentation.

- The second step involves preparing the final server - small and fast, containing only the necessary programs or libraries to run the compiled files.

As in the previous example, let’s create another Docker file Dockerfile_v2 and start coding.

###################################

# build compilation image

###################################

FROM node:22 AS build

WORKDIR /app

COPY ./package.json /app/package.json

COPY ./package-lock.json /app/package-lock.json

RUN npm install

# copy rest of files and build

COPY . .

RUN npm run build

RUN ls -al /app/_site

###################################

# Building final image

###################################

FROM nginx:1-alpine3.20

RUN mkdir -p /usr/share/nginx/html

COPY --from=build /app/_site /usr/share/nginx/html

RUN ls -al /usr/share/nginx/html

COPY nginx.conf /etc/nginx/nginx.conf

EXPOSE 80/tcp

CMD ["/usr/sbin/nginx", "-g", "daemon off;"]

# vi: ft=dockerfile

So here we created the first build compilation where we execute our build. And right after, we’re building a final image, and only that last build will be used in the final image.

One last thing that we still need to add for our configuration. Do you see what’s missing? Yes, it’s our new nginx configuration without which our server wouldn’t be able to serve our content properly.

Let’s create the last nginx.conf file for our jsdocs. The full configuration can also be found below.

user nginx;

worker_processes auto;

events {

worker_connections 1024;

}

http {

include mime.types;

# remove nginx version from server header

server_tokens off;

access_log /dev/stdout;

error_log /dev/stdout info;

# opt file nginx async filehandling

sendfile on;

keepalive_timeout 65;

server {

listen 80 default_server;

# location of static files to serve

root /usr/share/nginx/html;

location / {

try_files $uri $uri/ $uri.html $uri/index.html /index.html =404;

}

}

}

All done together and now we can get into the last part, the build of the final Docker image.

docker rm jsdoc-offline; docker build -f Dockerfile_v2 -t jsdoc:latest . && docker run --name jsdoc-offline --rm -p 9002:80 jsdoc:latest

Comparing images and final conclusion

So now let’s compare what we actually gain from using a bit more complex way rather than the fast and dirty method. I am actually quite curious if you can estimate what will be the size of both images without knowing it yet.

But let’s not prolong this, and the final results you can find below for my local builds (M3).

→ docker images jsdoc-dirty:latest --format "{{.Repository}}:{{.Tag}} -> {{.Size}}"

jsdoc-dirty:latest -> 1.85GB

→ docker images jsdoc:latest --format "{{.Repository}}:{{.Tag}} -> {{.Size}}"

jsdoc:latest -> 77.6MB

As you can see, the fast and dirty image is quite big, and to be precise it is 2.384% larger than the more efficient version. So now you see why the efficient way is much better for end customers like us, especially when downloading bandwidth matters the most.

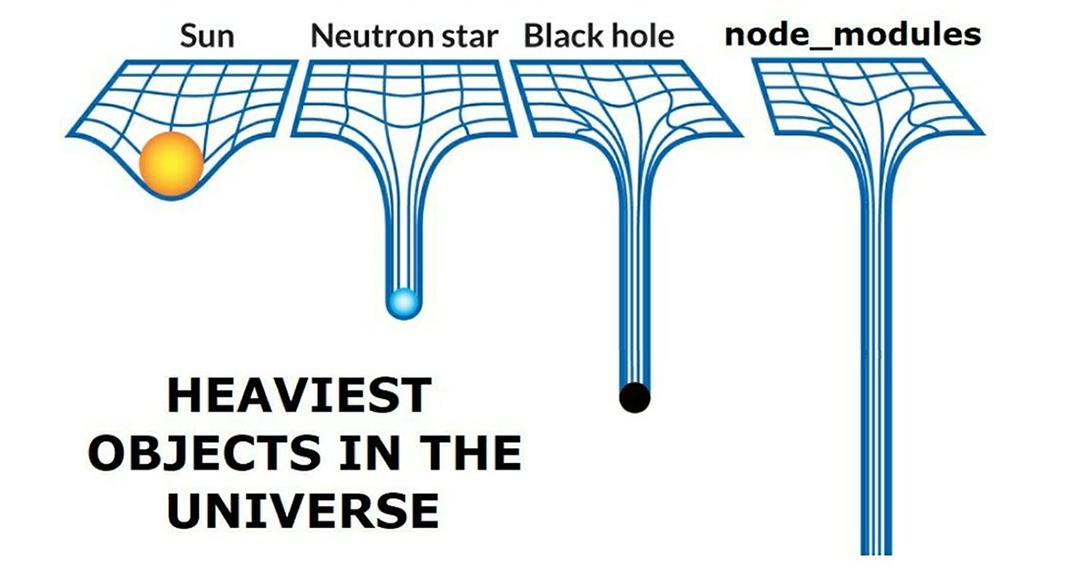

The results could be quite shocking for those who might not have realized before how big a dev server can be - especially those who run on npm and node_modules. I apologize, I couldn’t rest, but you may see for yourself downloading some of the images that must running with node servers (I am looking at tailwind and mui!).

Thank you for your time, staying with me and reading until the very end. Hope you find this enjoyable. See you until the next one.

Offline docs

Here is also a little hint (for me in future) how to quickly setup and build images for multiple architectures on Mac M-serie.

# create new builder

docker buildx create --name mybuilder --use --bootstrap

# should list new mybuilder image

docker buildx ls

# build images and push to repository

# INFO: progress plain is optional. This option give some additional debug options while building images

# INFO: if build take a while, then build separately and then push with with

# all platform set at once, otherwise one will override another

docker buildx build --push --platform linux/amd64,linux/arm64 --tag <docker-user>/<tag-name>:<build-version> --file Dockerfile --progress=plain .

Final images to download and use

I compiled the images for two architectures: arm64v8 and amd64. Those are sufficient for most users, although if need more, just let me know in the comments.

-

jsdoc (eleventy, npm) ~19MB compressed

docker run -d -p 9001:80 egel/jsdoc:latest -

svgomg (gulp, npm) ~20MB

docker run -d -p 9002:80 egel/svgomg:latest -

tailwind (nextjs, npm) ~4GB

docker run -d -p 9003:8080 egel/tailwind:v3 -

material-ui (node:22, react, pnpm) ~1.68GB

docker run -d -p 9005:8080 egel/mui-docs:latest -

react hook form (node:22, nextjs, pnpm) ~600MB

docker run -d -p 9006:8080 egel/react-hook-form-docs:latest -

react icons (node:22-alpine3.21, astro, yarn) ~1.14GB

docker run -d -p 9007:8080 egel/react-icons:v5.4.0