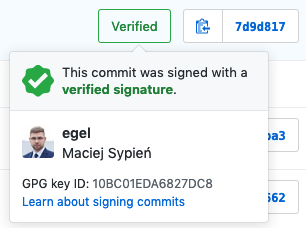

When I saw for the first time a commits with the mysterious “Verified” sign and I was told that someone can do this on its own, I wanted to do the same. Yes, I know it was silly - but I felt just like a small boy in a big shop of toys.

After a moment when I was informed about this cool function, I started to wonder:

- Ok… but what exactly those verified commits really are for?

- Why should I sign my commits with this PGP key? I already use SSH private/public keys.

So to answer those questions, I did some queries on Google and found: “Why would I sign my git commits with a PGP key when I already use an SSH key to authenticate myself when I push?”. The post gave me a reasonable answer to why we should sign commits or at least sign the tags.

Ok, but to the most important question for me at the time was:

Why and what for I should sign my commits?

In order to answer, we must start from the very beginning.

“When you authenticate to Github with your SSH key, that authentication doesn’t become part of the repository in any meaningful or lasting way. It causes Github to give you access for the moment, but it doesn’t prove anything to anyone who is not Github.” - HedgeMage.

The author made a relevant point, which is true. When you log in to any repository (Github, Gitlab, whatever…) you have to have an account, which is used by somebody. Exactly, it doesn’t mean that “you” is really you - by having an account it means that you can see/do stuff in this place. Definitely, it’s not saying that let say, John Doe from Pima County Cemetery, Tucson, Arizona is really the John Doe.

Then comes the SSH.

“SSH is a cryptographic network protocol for operating network services securely over an unsecured network.” - Wikipedia

In this short definition (and also in further part), there is no phrase, which could indicate correlation between a digital identity and a person who use SSH tunnel. SSH is focusing on the machine from where some mystical person X use this secure shell connection in order to get access to server X. So… How this corresponds to the original problem of securing the commits?

We have come at last to the place where the PGP keys enter to the scene. A creation of the aforementioned PGP keys and obligatory making them public in a trusted, available to everyone place, should give to the world (in definition) a certain assurance that “you is really you”. Only the person who has private and the public key can sign the data with that key, e.g.: someone using your public key can encrypt the his message and only you, the person with corresponding private key could decipher the message. Finally, the last and IMHO the hardest part of that process, to use those keys wherever possible to emphasize that “you is really you” or in our case, “you, not someone else who is claiming to be you” created this commit.

Before you do same, what the funny character from the cartoon already did, I want to show you a story why you should sign your commits (especially for programmers, which the creation of commits determine a daily basis) and what might happen in negative scenario when you will not sign them - A Git Horror Story: Repository Integrity With Signed Commits.

Open sesame!

Disclaimer: the tutorial presented below has been made for OSX, but it should also be valid for Linux work stations. The idea is completely the same, only the name of some tools to generate keys or 3rd party libs might change.

Additionally and intentionally I didn't write directly my email address and I used a fake john.doe@gmail.com email.

To secure your commits, you will need:

- git (user apple Xcode tools or install via brew

brew install git) - gpg (important to use version 2, install via

brew install gnupg) - dirmngr (it should be a part of gnupg installation via brew)

- repository to store public keys (e.g.: Github, Gitlab)

PGP key

Let’s start with creating your PGP key. You will use it to secure/identify the content has been made by you.

If you already used some configuration and see something like:

gpg: Sorry, no terminal at all requested - can't get inputThen go

~/.gnupg/gpg.confand temporally commentno-ttyoption that block creating anything on machine (for security purpose, after this enable it again)

gpg --full-gen-key

You will get few questions to answer (e.g.: name, email, comment, passphrase) which will be stored in your key and visible to everyone (it’s not a good place to make jokes there - would you trust the clown 🤡? - me not 😉).

Note: Personally, I do not recommend an empty passphrase and I'm opting for a 4096-bit key. The passphrase can be easily stored in gpg-agent for a desired period of time (e.g.: 1 day, 5 days, or more), so you do not need to type it all the time when signing something.

Then we have to get a reference to your key so the git will understand which key he has to take in order to sign each commit. Below command will give them the list of all your public keys in the system, select the one you have entered.

gpg --list-secret-keys --keyid-format LONG <your-email>

Now you can take the PGP key ID to use it in Git. In my case, the key looks like this:

gpg --list-secret-keys --with-fingerprint --keyid-format LONG john.doe@gmail.com

sec rsa4096/EFJNQD3VCBZZBB9M 2019-03-17 [SC]

CY2U VVNI HKVX JGOP QIWU E2NW EFJN QD3V CBZZ BB9M

uid [ultimate] John Doe <john.doe@gmail.com>

ssb rsa4096/EBEE77C5734494A6 2019-03-17 [E]

Use the PGP key ID, in my case, was EFJNQD3VCBZZBB9M.

Ok, we have got the key, now we need to get your public key to make it public (anywhere, somewhere!).

Below command will store the key to file and save it in your home directory.

gpg --armor --export <your-email> > ~/public_pgp_key_your_name.asc

We will get back later to GPG again in second when we get to the software configuration section.

Git

Now configuration of your git config file should be set up via below commands:

git config --global user.signingKey EFJNQD3VCBZZBB9M

git config --global commit.gpgSign true

Repository

Remember the public PGP key we have created? Now open your repository on “GPG keys” section (it should be called PGP, but this is a topic for a different story) in order to upload your private key and then you’re almost done.

Now, Git is able to sign all your commits automatically with defined key. Your content can be with “a reasonable assurance” confirmed that you are the author and did this work! Wicked!

Software configuration

I said before “you’re almost done” because, for me, the full tutorial require recommended/explained configuration of the software presented to fully gain from the lesson.

So what we can configure here?

-

For some people might be important to not enter the PGP passphrase every time they want to create a commit. To do so, we have to changed some default configuration of gpg (or gpg-agent, which I prefer). For example, if you set up the ttl to: 5184000 (60 days), after first successful sign, GPG won’t ask you again to fill the passphrase until this period will expired (or until you’ll restart your machine)

It's not recommended to make the cache expiration long unless you know that this might reduce your security.

# ~/.gnupg/gpg-agent.conf # Set the maximum time a cache entry is valid to n seconds. After this time a cache entry will be expired even if it has been accessed recently or has been set using gpg-preset-passphrase. The default is 2 hours (7200 seconds). max-cache-ttl 2592000 # 2592000 = 1 months # Set the time a cache entry is valid to n seconds. The default is 600 seconds. Each time a cache entry is accessed, the entry’s timer is reset. To set an entry’s maximum lifetime, use max-cache-ttl. Note that a cached passphrase may not be evicted immediately from memory if no client requests a cache operation. This is due to an internal housekeeping function which is only run every few seconds. default-cache-ttl 2592000 -

Use a secure program to enter your pin/passwords, like e.g.:

pinentry.In order to install pinentry on OSX use brew:

brew install pinentry-mac # check where pinentry-mac is stored which pinentry-mac /usr/local/bin/pinentry-macThen add the following configuration to your gpg-agent.

# ~/.gnupg/gpg-agent.conf # Use following program as the PIN entry. pinentry-program /usr/local/bin/pinentry-mac -

Better GPG configuration with dirmngr

# This tells gpg to use the gpg-agent use-agent # Make sure that the TTY (terminal) is never used # for any output. no-tty # Ensure that all keys are refreshed through the keyserver you have selected. keyserver-options no-honor-keyserver-urlSince the gpg configuration deprecates

--keyserverand an option in favor of usingdirmngr.confand set up those options there.This option is deprecated - please use the

--keyserverindirmngr.confinstead. Here you have a reference link.# ~/.gnupg/dirmngr.conf # --keyserver URI # # GPG can send and receive keys to and from a keyserver. These # servers can be HKP, Email, or LDAP (if GnuPG is built with LDAP # support). # # Example HKP keyservers: # hkp://keys.gnupg.net # # Example HKP keyserver using a Tor OnionBalance service # hkp://jirk5u4osbsr34t5.onion # # Example HKPS keyservers (see --hkp-cacert below): # hkps://hkps.pool.sks-keyservers.net # # Example LDAP keyservers: # ldap://pgp.surfnet.nl:11370 # # Regular URL syntax applies, and you can set an alternate port # through the usual method: # hkp://keyserver.example.net:22742 # # Most users just set the name and type of their preferred keyserver. # Note that most servers (with the notable exception of # ldap://keyserver.pgp.com) synchronize changes with each other. Note # also that a single server name may actually point to multiple # servers via DNS round-robin. hkp://keys.gnupg.net is an example of # such a "server", which spreads the load over a number of physical # servers. # # If exactly two keyservers are configured and only one is a Tor hidden # service, Dirmngr selects the keyserver to use depending on whether # Tor is locally running or not (on a per session base). # keyserver hkp://pool.sks-keyservers.net # DEPRECATED DO NOT USE keyserver hkps://keyserver.ubuntu.com # --hkp-cacert FILENAME # # For the "hkps" scheme (keyserver access over TLS), Dirmngr needs to # know the root certificates for verification of the TLS certificates # used for the connection. Enter the full name of a file with the # root certificates here. If that file is in PEM format a ".pem" # suffix is expected. This option may be given multiple times to add # more root certificates. Tilde expansion is supported. # hkp-cacert ~/.gnupg/sks-keyservers.netCA.pem # This option enables OCSP support if requested by the client. # # OCSP requests are rejected by default because they may violate the privacy # of the user; for example, it is possible to track the time when a user # is reading a mail. allow-ocsp # Append all logging output to file. This is very helpful in seeing # what the agent actually does. Use ‘ socket://’ to log to a socket. log-file /var/log/dirmngr/dirmngr.log

Secure your private and public keys

After creating new pgp keys, when it are still new and shing it is recommended to secure your keys, together with you passphrase! Store all of them them in a save place (e.g.: in your password manager or print it on the paper and store in save place). Otherwise if you loose the private key or loose passphrase you may regret not doing it.

To create a file with public key you do:

gpg --output public-key.pgp --armor --export username@email.com

then export much more valuable private key with command:

gpg --output private-key.pgp --armor --export-secret-key username@email.com

Optional publish your key

If you want that your key to be recognized by others, or to communicate with you, you can send your public key to some servers. But before this make sure to create revocation certificate! Do not ignore it as if your key has unlimited expiry period and after uploading to external servers you will loose it (key or passphrase) it will be almost impossible to get it back.

gpg --keyserver keyserver.ubuntu.com --send-keys yourkeyID

then you can check if the server has the key (it might take few minutes)

gpg --keyserver hkp://keyserver.ubuntu.com --search-key 'username@mail.com'

Awesome! Now you have a complete overview and good configuration to start working. Have fun and stay secure!